Assume breach: The cyber threat 2 traders

Assume breach: The cyber threat to traders

From Modern Trader Magazine October 2015 Issue

This is a story about cyber security and its effect on traders.

It’s about vulnerabilities in a financial system that over-relies on technology to make trading faster and more efficient.

For traders and investors, the desire for ease-of-use and functionality that expedites buying and selling has been developed by application developers who typically underestimate security risks.

For brokerages, investment firms and exchanges, cyber security has become one of the most important concerns of the 21st century. The July software glitch at the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) immediately reminded traders of the 2010 event in which Russian hackers placed a “cyber bomb” on the Nasdaq.

It never detonated, but it’s curious that it took four years for government officials to conclude their investigation and release information to the media. Cyber attacks are a sensitive topic.

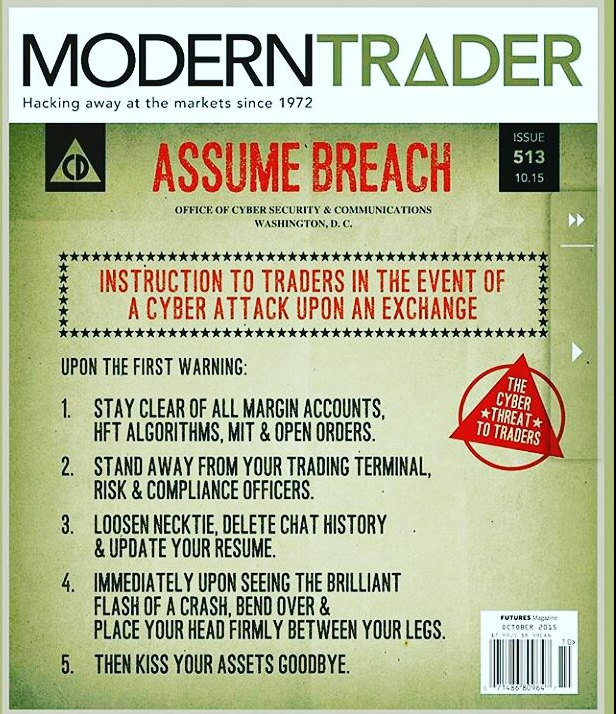

No company wants to admit that it has been hacked. No exchange wants to divulge the reality that hackers are constantly looking for vulnerabilities in their systems. And no one wants to explain to traders how they should react after a breach in the markets.

It’s time to have an honest conversation about cyber security.

What are the risks in the future, and, more importantly, what can traders and investors do to ensure they are taking the right steps to protect themselves?

For that answer, Modern Trader took an unconventional approach to understanding the future of cyber security and the threats knocking on the door.

Recently, four hacking experts sat down in a bar proximate to the Chicago Board of Trade to discuss the current threats to our financial system, the simplicity of a possible attack on networks and how they might attack any public company in America, and more importantly, “Why?”

The four representatives are part of a group of “ethical hackers” with global reach aiming to educate financial companies and share their thoughts and concerns about the international cyber security industry.

What follows is a conversation about the markets, cyber security and the coming challenges that investors and traders face in the 21st century economy.

The first round

Four “ethical hackers” sit in a South Loop bar in Chicago, ordering cheeseburgers and beer.

The meal will provide fuel to speak candidly about current threats to the global financial system, trading firms, brokerages and, most importantly, individual traders and investors.

The questions are simple to start: “What were your first thoughts about the July software glitch at the New York Stock Exchange?”

No hesitation preludes an answer. Each expert knows the details. On July 8, trading on the NYSE was suspended for three hours and 38 minutes after the technology underpinning the exchange was compromised by a software malfunction. On the same day, the website of The Wall Street Journal was also offline due to a technical glitch and United Airlines grounded flights for two hours thanks to a similar malfunction.

Terry Bradley, chief technology officer and director of cyber security solutions at PLEX Solutions based in the Washington, DC area, speaks first. “I didn’t want to say it. But it was an enormous coincidence,” he says as he scans the beer menu. “But not everyone wants to cry wolf when something like this happens.” Bradley, a 1990 graduate of the Air Force Academy, started his career in the Department of Defense.

To his left sits Mr. Orange, an elite security specialist who builds systems that allow critical data to be shared across different security environments. Mr. Orange is building his consulting practice and wishes to speak under a pseudonym because he is engaged in several projects that require anonymity. He keeps his thoughts tight and to the point, “I thought, ‘Who screwed up with a fat finger?’”

Next is Erdal Ozkaya, the chief information security officer of Secunia and vice president of emt Distribution, based in Dubai. A prolific speaker and security specialist, it’s clear why his presentations are popular in the cyber community. His language and personality are supercharged when discussing security. Each answer comes as if it’s been shot out of an electric socket.

“The first thing that comes to mind when these events happen is that it’s a cyber attack from China,” says Ozkaya.

Finally, there’s Mr. Green, a global security consultant spearheading a number of financial certification programs and forums on global cyber security in the banking and defense sectors. He has asked to use a pseudonym because of his current client work as well as his blunt analysis.

He shakes his head and smiles coyly at the thought of the NYSE, The Wall Street Journal and United Airlines all having software glitches on the same day. “Three companies all at once,” he says, leaning in. “I thought, ‘Wow, they’re [screwed]. And they don’t know how much right now.’”

The glitch has been called “coincidental” by government officials. An investigation is ongoing, but it’s clear at this table and across multiple digital media outlets that the full story hasn’t been told.

Regardless of whether the NYSE glitch was nefarious or not, the financial markets now exist in a world where cyber threats are the new normal. In 2010, Debora Plunkett, who then headed the U.S. National Security Agency’s Information Assurance Directorate, said bluntly, “There’s no such thing as ‘secure’ anymore.”

The NSA — and ultimately brokerages, exchanges and other financial companies — have adopted a philosophy that shifted to an assumption that information networks and security systems already have been compromised.

“Debora Plunkett came up with this idea of ‘Assumed Compromise,’” says Bradley.

Unfortunately for Plunkett, that philosophy — grounded in rationality and honest about the current threat environment — didn’t help her maintain her position at the NSA. A new position was created for her in 2014, but this table doesn’t think it was because the NSA needed a new Senior Advisor for Equality.

“They got rid of her for being too negative,” says Mr. Green. “She was just trying to speak sense to the industry. She knew the reality of the world we live in.”

The idea of an assumed breach is just the beginning of a broader conversation about the digital reality facing traders, investors and anyone connected to a digital network. But first, an important lesson must be understood about the cognitive nature of hacking.

Ask a cyber expert in Washington or a chief information security officer (CISO) at a company why hackers break into financial companies or exchanges. Or ask why this idea of assumed breach is now the norm for society today. The near-universal answers will lie in either the desire for data, money or a nefarious actor engaged in nation-state terrorism. But there’s a more simple answer as to why hacking occurs and why the markets face an increase of potential threats, according to Ozkaya.

“These [financial] systems are made by humans,” he says.

Why do hackers do what they do?

Because they can — thanks to the weakest link of any organization: the human element.

The hacker’s mindset

A round of beer arrives. Ozkaya smiles and pulls out the camera on his phone.

The beer he orders is brewed at a facility not far from his former high school in Germany.

Born and raised in Germany, but of Turkish descent, Ozkaya has advised Microsoft Corporation (MSFT) in Redmond, Wash., spearheaded security initiatives at casinos in Las Vegas and led IT security for his firm in Dubai. He’s pursuing his PhD in IT Security from Charles Sturt University in Australia.

The bar is crowded for a Thursday night, every stool is filled as the post-work crowd watches the Chicago Cubs play the Milwaukee Brewers.

Citing the research of Timothy Summers, an expert on cognitive hacking, the next question on the table is simple: “When you look at this crowded bar, what vulnerabilities do you see?”

Bradley and Mr. Green begin to speak, but Ozkaya springs a finger into the air. “I’d like to answer that first,” he says. He turns to the front door, where a party of five is asking for a table. “When I look around, I notice there’s only one exit door to this building. If someone were to put up on a screen that there was a terror attack or a threat in this room, people would rush out of the bar — they might trample over each other.” He adds, ”If someone posts on Twitter that a bomb threat or terrorist threat is imminent, that spreads across social media right away.”

It’s a terrifying introduction, but it’s also based on previous incidents. Just two years ago, a hack of the Associated Press’s Twitter account claimed a bombing in the White House. The stock market slumped more than 140 points, and every media channel ran with the story with little verification. It was real-time information discovery company Dataminr that determined the hack was a fraud by triangulating Tweets of other individuals in the proximity of the White House.

The media finally recognized the hoax.

The other men at the table are nodding in agreement that patrons in the bar likely didn’t check for the fire exit sign in the back of the bar when they entered.

“Wow, that’s intense,” I say, shaking my head. “I thought you were just going to tell me that you could turn off the televisions without anyone noticing.”

A laugh follows. “Oh,” one of the four men says, nodding to the wall. “I can do that too.”

Behind the table, two of the three televisions previously airing the Cubs game have been shut off. The prankster smiles, awaiting the next question.

Traders on edge

In August, Australian authorities thwarted several Russian hackers who allegedly breached CommSec and E*Trade accounts and purchased shares without customers’ knowledge.

In an interview with the Australian Broadcasting Channel (ABC), Greg Yanco, who supervises the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), said the hackers sold blue chip shares in each breached account. By building up a large pool of liquidity, they bought and bid up stock prices of shares already owned in the portfolios. After prices hit a specific level, the hackers sold everything at market through their own trading accounts.

“This is a relatively sophisticated attack because the perpetrators have discovered customers with online broking accounts and they’ve used that to alter the share price to their own advantage,” Nigel Phair, internet safety director at the University of Canberra, told ABC.

Authorities recognized the unusual trading behavior before the positions were settled. A judge froze more than $77,000 in illicit profits from being exported from the country. Given a three-day period to clear each transaction before money can be transferred, authorities are always looking for unusual patterns. ASIC contacted the hackers to discuss their withdrawals, but received no reply.

Despite successful work by authorities, Yanco admitted the ASIC’s success won’t improve security of online brokerages from future breaches. “Our first line of attack, I guess, defense, is to really hold that money and absolutely deter people from doing this again,” he told ABC.

At the table, the four hacking experts explain that attacks are going to grow only more complex and elaborate in the future. “[Traders] need to understand that the cyber world is different than the physical world,” says Bradley.

No longer is money protected solely in vaults. It’s spread across digital accounts. It’s now being transferred through cloud networks. The digitalization of money has heightened security vulnerabilities.

“In the 1960s, if you wanted to break into a bank, criminals needed weapons, a getaway car and a strategy to get past other men with guns,” says Ozkaya. “Today, all you need is an Internet connection and a [hardware] device. It’s just a process of using the online [access] and exploiting systems and humans in order to achieve their grand heist.”

Following the attack on Australia, Nigel Phair offered antiquated advice on how traders can protect their accounts. “Good solid passphrases that contain numbers, letters and symbols [are] a good way to go,” he told ABC.

Solid passphrases? Letters and symbols?

When they’re mentioned to this group as proposed solutions to cyber security, Bradley tinkers with his phone as he explains that that’s not enough.

How to hack an institution

Hollywood has created a projection of what it thinks hackers look like. The typical character is either a skinny 20-something with a streak of green in his hair, or a single geeky tech nerd full of paranoia and anti-government angst.

No one at this table resembles these stereotypes.

Bradley is soft-spoken and looks like he’s more suited for hosting a backyard barbeque than hacking client security networks from a back office. The mischievous smile of a man who feels that he’s being paid to misbehave appears.

After unlocking his phone, he clicks a few buttons. Then, he holds up a black screen with a flurry of multicolored lines that resemble a series of bell curves. The highest bell curve line is pink and has the restaurant’s name floating beside it. There’s another line, red, which features the word Xfinity, the name of a Comcast Wi-Fi hotspot. Several other lines are flatter. This screen doesn’t appear impressive, but it’s a hacker’s treasure trove. “This is the strength of every Wi-Fi signal in this bar right now,” Bradley says.

The bar has its own Wi-Fi network for guests. There’s no security; no password required. Patrons can connect their computers or phones, check sports scores and sign into their e-mail.

“There are two options. I can either watch the data coming over the open network, or I could create an open network of my own through my phone or another device and allow users to sign on to my network.”

It sounds innocent. But Bradley explains a scenario that could be troubling for any financial company within the Chicago Loop.

“We’re just a few blocks away from the CBOT and the offices of trading companies. What do you think the odds are that someone who works in one of these companies or exchanges might be in this bar right now [or any bar in the area]? If they sign on to my network, I’m seeing and collecting their data. If they sign into their work e-mail or trading accounts, I can see everything,” he says.

That includes passwords and vital network configuration data. One person checking his or her work e-mail on an unsecure network can provide a welcome mat to a would-be attacker.

It only takes one person.

As Mr. Green explains, many companies don’t realize that their vulnerabilities are actually at the peak when employees leave the office. “Employees are ready to go home. Maybe they come to a bar, have a drink and their phones or devices connect to a network. Sometimes, their phones might connect without them knowing. That’s when a company is actually the most vulnerable.”

New generations of phones and networks have facilitated easy connection between devices. Sometimes, a phone might automatically connect to a network like Xfinity simply because a user has signed into a hotspot in the past and casually clicked a link that instructed the phone to “Don’t Ask Again” when trying to connect to that network in the future.

Or, users just blindly connect to an open network with the name of a nearby restaurant or company without realizing that it could be fake and designed to collect a person’s data without their knowledge.

What good are strong passwords with letters and symbols if someone can obtain this data through alternative means? Bradley explains that by gaining access to sign-in information for an employee’s work e-mail, it’s possible that he can exploit any configuration weakness in a company’s network to target the data of executives in the company, the firm’s software or trading applications, its finances or any other place where security is deemed vulnerable.

“That’s just one way to do it,” Mr. Green says.

There are other ways to attack a company. Some so simple, it invites paranoia.

“You could just park your car in front of the CFO’s house and break into his home network,” Bradley says.

Then, there’s the long-con.

“Or you can target the CFO’s secretary,” Mr. Green says, with a short laugh.

Bradley’s leans in and smiles. Mr. Orange too.

Then Ozkaya grins. Turning the interview on the interviewee, he asks, “Are you on Facebook?”

Not after tonight.

What about bob?

Anyone seeking to breach a company’s critical data and gain sensitive information has one holy grail in mind.

“The CFO is undoubtedly the target,” says Mr. Orange. “And all information is vulnerable in ways that he or she couldn’t imagine.”

What follows is a simple example into the cognitive gymnastics of how four brilliant tech minds can exploit the vulnerabilities of a financial firm. The exercise is so fast-paced and so vivid that the conversation and ensuing hacking scenario could have been devised at an advanced improv cass at Second City Theater.

This scenario is not based on speculation. Rather, it derives from the accumulation of their combined decades of experience. All too often, they’ve seen this exercise in social engineering.

For their discussion, they invent a CFO.

His name is Bob.

Bob runs a mid-tier bank with a lot of assets. He is convinced that his security system is in place. He makes sure he doesn’t use his e-mail on any other devices except for his phone and his work computer. He’s successful, he’s smart. He has an MBA. He’s married. He makes a lot of money.

“Bob isn’t worried about security,” Mr. Orange says. “Because Bob says that he hires the best security people. They tell him all the time that they ‘have his back.’ He’s telling himself, ‘My IT guy is the best.’”

Mr. Green smiles, reflecting on a statement that he’s likely heard all too often during his conversations with executives about security. “Bob also says that he pays his IT staff enough money.”

Bradley points out that they’re going to use data to gather more data, and they’ll try to find a way to access Bob’s e-mails or exploit his contact list in the organization. In Bob’s mind, he’s operating in that impenetrable stone castle with a moat and no structural weaknesses. There’s no shortage of confidence.

But as the story weaves, it turns out that Bob has an assistant. Her name is Debra.

The hackers might kick off an operation by targeting the assistant. The hackers spend a few hours gathering more information on Debra. They create a profile on her. By finding Debra on Facebook, they discover she’s a grandmother from pictures and shared links. She loves her grandson. She also likes dogs.

Most important, Debra isn’t considering the importance of cyber security at her company. From the way she openly posts information about herself and others, privacy doesn’t seem to be a concern of hers. She might live in a nice neighborhood, but she doesn’t realize how unsecure the Internet actually is.

So, the hackers spoof an e-mail to make it look like it was sent from someone she knows.

“[We’ll] send her an e-mail saying, ‘Hi Debra, it’s your [cousin Laura]. Here are some pictures of your grandson [from the party].’ And it will include a link.”

When Debra clicks a link, the team has breached her computer and contact list through malware. With a few clicks, they’re able to access her e-mails, and, more importantly, people that CFO Bob has asked her to contact on his behalf.

The hackers can stop there, given that they know whom Bob is communicating with, or they can go deeper and access Bob’s e-mail because of their ability to exploit the configuration of the e-mail system.

Maybe they find a conversation about a merger. Maybe it’s an e-mail exchange with a bank to discuss the transfer of money from the company’s accounts. And maybe they can trade on this inside information.

From the surface, it appears to be just another dream scenario.

Bradley unfolds his hands and reaches for his beer.

He’s seen this scenario more than once. As a cyber-assessment consultant, his job is to identify vulnerabilities long before someone else does. Hired by firms in finance, retail and other sectors, he’s seen no shortage of naiveté when it comes to IT security.

“We conducted an assessment of a company a few weeks ago,” Bradley says. “When we arrived, word had spread throughout the company that we were there. Employees were taking their batteries out of their phones. They were whispering that we were trying to break into their systems. Some people were also saying that it didn’t matter if they were compromised because they were nobody in the organization. But even one user account with access to the organization’s network resources is very valuable. On that project we were able to steal a low-level employee’s password and, because of the way their network was configured, access the CFO’s computer with just that password. In fact, anyone in the company could have done it, but no one ever thought to check — that’s what we do.”

Bradley explains that it’s not just data from the one client’s company that his team could access.

“When we told [the CFO] we accessed his computer, blood drained from his face. There was personal data. There were files and e-mails from past companies that he worked for. There was very sensitive information.”

And there’s no shortage of dangers of what could occur if this data falls into the wrong hands.

Front running

Mr. Green is dressed in a dark blazer. He has the look of a man who just stepped off a yacht, but listening to him explain the darker side of hacking, it’s not clear that the yacht on which he may have arrived is his own.

Somewhere, another man might be missing a boat.

“You know what’d be interesting?” he asks as dinner arrives and a lull hits the conversation. “What if I took a Raspberry Pi (credit card–sized single-board computer) and shut down Hartsfield Airport in Atlanta?”

There’s little shock or surprise at this statement. In fact, the four men are in agreement that there are vulnerabilities in airports or anywhere that provides open Wi-Fi access. Mr. Green explains the process by which it’s possible to do this. It includes the use of multiple Raspberry Pis.

How long would it take to take an airport offline?

“With one or two people, with a lot of planning, it could be done in two weeks,” Mr. Green says.

But, why would someone want to shut down an airport? Why even ask? The answer is money.

Following the software glitch at United Airlines, the stock declined more than 2.7% from its opening price to its intraday low. Hitting an entire sector could cause a temporary disruption of flights across the country.

A three-hour hack likely would create more panic than, say, a giant snowstorm that shuts down an airport for days. Investors aren’t used to the increasing likelihood that large breaches will grow more frequent.

Snowstorms come and go. A few hundred dollars in equipment and a few thousand dollars in stock puts could be timed for a future date. That’s the nature of each potential breach. There isn’t a schedule or an estimate on timing.

“The markets are centered for results each quarter. But hackers, they have no time frame,” says Bradley. “They’ll wait several months to plan the attack.” And they’ll collect money on the backend.

Mr. Green’s example is an extreme scenario. There’s a lot of work involved, and a mixture of both havoc creation, and quite an extreme to make some money in the stock market. But it’s a tiny slice of the lengths that some cyber criminals are going to in order to make money manipulating the stock market.

As Mr. Green explains, investors should pay attention to the work of hackers that is already affecting stocks.

“Let’s talk about Avon,” says Mr. Green. “The stock popped on a takeover bid, and we came to find out that the potential buyer of the stock was fake — it said the private equity buyer was on an island in the middle of the Indian Ocean.”

Mr. Green is referring to a May breach by a Bulgarian man called Nedko Nedev. According to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Nedev was able to move the price of Avon Products’s shares by as much as 20% by filing a fake report through the agency’s Edgar system. The filing said that a non-existent private equity firm called PTG Capital planned to purchase the publicly-listed cosmetics giant for $18 per share. The stock’s market capitalization surged by $600 million.

Months after this breach, the SEC said it won’t make any modifications to the Edgar filing system. The SEC oursourced security responsibility to public companies.

“Filers are responsible for the accuracy of their filings and, as demonstrated, face enforcement actions for false filings,” an SEC spokesperson told Business Insider. This philosophy will force companies to add additional layers of security to the process, and will require continuous monitoring of any filings made, despite the fact that the risk might actually be the fault of a vulnerable Edgar database.

Reports and news stories issued by cyber criminals have affected the stock prices of several companies.

Twitter (TWTR) shares have moved because of stories reporting false takeover bids. In 2003, Sina Corp. (SINA) saw its share price fall after Nikolai Safavi issued a fake Reuters story that reported Goldman Sachs had initiated coverage of the company with a “market underperform rating.” (Safavi was caught and paid a $25,000 fine after making just $350 shorting the stock.)

Meanwhile, Business Wire, which ran a fake press release in 2010 about a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that favored Javelin Pharmaceuticals (JVPH) and subsequently moved the stock prices, changed its submission process. Today, it requires password-protected submissions to ensure that any press release will come from the actual client and not from someone running a scam.

It might seem like enough, but as Mr. Orange soon explains, an important question must be asked.

Once the password is typed in, how will Business Wire or Edgar verify this information?

Verify & clarify

Mr. Orange is building his business and his resume quickly, recognizing that his area of focus is perhaps the most important for individual traders and investors who are concerned about the areas in cyber security in which they maintain control.

Ensuring greater protections for traders and investors likely will require the institutional side to adopt best practices and assess their security protocols tied to verification of money transfers.

“Non-repudiation is critical for networks moving forward. Whenever someone makes a trade, whenever money is transferred, there needs to be greater verification,” he says. “That way there is no way that it isn’t you logging into a system and authorizing activities. When it comes to security, the first element is that you must trust the person or the system. But more important, you have to verify. Finally, you have to have an IT team show how they clarify information.”

Ozkaya explains that hackers made off with $1 billion thanks to simple phishing techniques targeting data across 100 different banks in 30 countries. Then, there’s the scenario in February when a cyber-gang called Carbanak was able to hack ATMs and have them dispense cash at pre-determined times.

All they had to do was walk up to the machines and collect the money.

Across all of these breaches, there’s one common problem. In cybersecurity, verification is so simple, but it’s very overlooked by application developers who are focused on functionality and ease of use. Verification processes work, although they can sometimes require a level of inconvenience to individuals who prioritize ease-of-use and functionality.

Recently, Stacy Francis, president and CEO of Francis Financial, told CNBC about an urgent wire transfer request she had received from a client in May 2015. A message came directly from a client’s e-mail address requesting an immediate wire transfer as she was preparing to board a plane to Colombia for a conference. By breaking past the client’s firewall, the hacker was able to access her contact list and request that her money be wired to a specific bank, including a routing number.

Then, the hacker sent a follow up e-mail that read, “Are you not in the office?”

Francis called the e-mails convincing, and said that the second e-mail tapped into the human element that advisors are worried that clients always think they’re out on the golf course instead of managing money.

However, she noted that the firm’s security protocols ensured that the breach didn’t lead to a loss for the firm. Francis Financial demands a notarized letter and a personal client phone call from the client before it transfers money to third party banks.

But, traders using online brokerages and digital platforms aren’t going to send a letter to their broker every time they want to make a trade. Unfortunately, for a client Bradley knows too well, they failed to have a verification process in place, and it ended up costing them everything in the bank.

“I recently met a client who was scammed for six figures. There was no hacking involved except for a spoofing e-mail from the CEO. It was sent to an assistant that asked her to transfer money to a bank account. Because the e-mail comes from the CEO, she does it. There were no procedures in place, no verification. This was a straight-up scam. To be honest, how much hacking skill does this actually take?”

Mr. Orange shakes his head slightly. “Not much,” he says under his breath.

The $4 million prank

One of these experts has turned off two televisions behind the table while he talks about the susceptibility of open networks.

“Watch,” he says, pushing another button. Over his shoulder, a 55-inch plasma television behind the bar shuts off.

Two rows of bar patrons, who just watched Chicago Cubs first baseman Anthony Rizzo whack a three-run home run, throw up their arms as the blackout disrupts the game. Two men point to the television. They call for the bartender, who turns away from other customers. The bartender inspects the television, checking its plugs. He turns the television on, pressing buttons madly, uncertain of what to do in this situation. The patrons are growing increasingly upset that they’re missing the Cubs rally while they’re eating dinner.

“The TV’s infrared technology is the same sort of tech that is used in guidance systems,” said Mr. Green. “It’s simply sending one code from a device to another device.”

The bartender is fumbling with the controller; he can’t figure out how to get the game back on, while the patrons try to help direct him on his DirecTV panel. Finally, he figures out how to turn the TV back on.

There’s a moment of calm — and then the prankster turns the TV off again.

It’s a cruel experiment, but it provides a stunning image of human reaction and confusion when technology fails to do what it’s been assigned to do. By now, the manager of the bar is pulling wires on the back of the television. The patrons have fortunately shifted two seats down the bar to watch the game on a parallel television, but the bartender remains confused as ever.

“This is the other part of what [occurs] when a breach happens. There is mass panic where you’re not sure what is going on,” says Mr. Green. “This is the aftermath. You’re seeing the confusion. People are pressing buttons to try to get something to work again, and sometimes they make it even worse.”

No one would expect a bar in the South Loop of Chicago to have a plan against a cyber attack, but for a hacker just looking to produce a bit of chaos, the stakes can be higher for a financial company.

“Imagine that each time a hacker turns something off it costs them $4 million a minute,” Bradley says.

The prankster looks back over his shoulder. The bartender again has turned the game back on, but he’s staring at his controller with a perplexed look. He takes out the batteries, stares back to the screen. A long pause fills the table. Finally, the prankster speaks: “Should I turn it off again?”

Self protection

Traders and investors face challenges that brokerages or trading systems don’t.

As consumers, new technologies are creating distinct vulnerabilities that allow hackers to target financial accounts, breach trading capital or exploit personal information.

“Baby boomers have saved all of their lives and now their money is more vulnerable than ever,” says Bradley. The proliferation of technology and the migration toward mobile will only lead to more advanced attacks and security threats.

“We’re moving closer to a scenario in a few years that individuals will be able to simply touch phones and take your information,” says Mr. Orange, citing the vulnerabilities in near-field communications. “A simple hack of a phone or program would make it easy to obtain an individual’s sensitive information, passwords, user names and financial information, without even touching a computer.”

Mr. Green explains that the rise of cellular phones has created a new vulnerability that no one seems to be talking about. “One of the biggest issues is that more applications are being designed to do things that they don’t need to do. When you download a flashlight app, it asks you for your location. Other apps that have no reason want to connect to your Facebook. Why does a flashlight need to know where I am? It’s clear that the app developers are selling your data.”

But someone selling data is the least of one’s concerns. There are many other ways that an attack can happen to an individual or a financial organization. And there’s the reality of how exploitable phones can be.

“I want you to read something,” Ozkaya says.

He opens a Samsung phone to the advanced settings in the “Backup and Reset“ function. Under the first tab, the screen reads “Back Up My Data.” He taps his finger off the check mark and a warning pops up.

It reads: “Stop backing up Wi-Fi passwords, bookmarks, and other settings and application data, and delete all copies from Google servers.”

It’s a common function, one already set as default on many new phones. While you’re using your phone and connecting to networks, the phone is automatically sending data, some sensitive, into the cloud.

That’s information — applications— that can easily be breached by the wrong individual if it’s continually backing up data across a network. Ozkaya suggests that the intersection of mobile technology and data aggregation has accelerated over the last five or six years and boosted the ability of companies and governments to track individuals.

Dig deep enough into your Google Maps settings, he explains, and you can see where you’ve been. (Ozkaya even taught a priest how to use Google Maps to challenge a parishioner on the date and time of his or her last confession).

“This is why I use a Windows phone,”Ozkaya laughs, suggesting his device isn’t an attractive device to target. “Not a lot of people use a Windows phone.”

So, what’s the safest way to ensure that financial information is secure?

Bradley’s philosophy might be a bit extreme for the average trader, but as both a cyber security expert and stock trader, he takes the most guarded method possible.

“I have a separate laptop for all of my financial obligations. That machine is all that I use it for. My bank accounts, my 401(K), my other investments. I don’t do anything financially related on my phone or on a separate computer. Now, I know that I’m not the average user.”

He’s not the only one. In June, Wired magazine profiled cyber security icon Dan Geer, whose early groundbreaking research introduced the economics of IT security to the world. As one of the most in-demand cyber experts in the world, Geer doesn’t carry a cell phone for privacy reasons and concerns about the complexity of mobile networks.

“We have repeatedly demonstrated that we can quite clearly build things more complex than we can then manage, our friends in finance and flash crashes being a fine example of that,” Geer told Wired.

Geer and Bradley are private individuals. And one might assume that they are not going to be a target on their individual networks. But that assumption would be wrong.

Recently, Bradley used a device to detect how many people are trying to get into his system on a daily basis. The answer: Roughly 30,000 to 40,000 attacks hit his personal home servers each day from programs or people trying to log into his system.

Bradley says he never clicks any link on his phone. Finally, he advises the importance of continuous router updates. “People don’t update their router. This is very important for people to check.”

The four hackers finish their beers. The check is paid. Very soon they’ll return to their jobs of discovering potential security breaches before someone else can. But they are still talking, still bouncing ideas and hypotheticals off one another. At some point they’ll have to sleep, but they’re well aware that the dangers exist 24 hours a day, and that hackers aren’t operating on nine-to-five schedules.

When asked for a final statement on how to protect oneself against the perpetual threat against one’s finances, it’s not a conversation about what technology to use or what security software to own. In the end, it all comes down to the philosophy of “verify and clarify.”

Bradley asks, tapping the table, “How good is your security? More importantly, how do you know?”

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/cyber-threat-traders-assume-breach-erdal-ozkaya/

Erdal in the news

https://www.erdalozkaya.com/category/about-erdal-ozkaya/media/

E

Great blog you have got here.. It’s difficult to find quality writing like yours nowadays. I honestly appreciate people like you! Take care!!

Excellent write-up. I absolutely appreciate this website. Keep writing!